by Pursuit | May 16, 2023 | Hunting

Turkey patterns constantly change during the Spring season, knowing what those are and what they might mean for your hunt can be critical in filling that tag. During the final week of May, turkeys may exhibit specific behaviors due to various factors, including breeding activity, weather conditions, and hunting pressure. Here are some key behaviors to consider during this time:

1. Breeding activity: By late May, the turkey breeding season is typically winding down, but there may still be some late-nesting hens and active gobblers. Toms might continue to gobble, but their response to calls may be less enthusiastic compared to earlier in the season. However, if you come across receptive hens, gobblers may still be in pursuit.

2. Roosting patterns: Turkeys generally maintain consistent roosting patterns, and during the final week of May, they may still be using the same roost sites as earlier in the season. Pay attention to where turkeys roost, as it will help you plan your morning setups.

3. Feeding routines: Turkeys will continue to feed throughout the day, with a focus on replenishing their energy reserves after the breeding season. Identify preferred feeding areas such as open fields, agricultural fields, or mast-producing trees. Turkeys will often travel to these locations during the late morning or early afternoon.

4. Increased wariness: As the season progresses and turkeys have experienced hunting pressure, they tend to become more cautious and wary of calls and decoys. They may be less responsive to aggressive calling and exhibit more skepticism towards decoys. Using subtle and realistic calling techniques can be more effective.

5. Adjusting to weather conditions: Weather can play a significant role in turkey behavior during late May. If the weather is warm, turkeys may adjust their activity patterns and feed more during cooler hours. Rainy or windy conditions may limit their movement and make them more likely to seek sheltered areas.

6. Changing habitat preferences: By late May, turkeys may alter their habitat preferences. They might move from dense cover used during the breeding season to more open areas, such as fields or edges of woodlands. Consider scouting to identify these transitional areas.

7. Hunting pressure impact: Turkeys that have experienced hunting pressure throughout the season can become more difficult to hunt. They might move to less-accessible areas, become more nocturnal, or change their patterns altogether. Adjust your hunting strategies accordingly, such as hunting quieter or less-pressured locations.

Observing turkey behavior in your specific hunting area during the final week of May is crucial. Spend time scouting, noting any changes in turkey activity, and adjust your hunting techniques accordingly. Adapting to their behavior patterns can increase your chances of a successful hunt during the closing days of the season.

by Pursuit | Apr 26, 2023 | Gear, Hunting

So you’re planning to go turkey hunting, well you should! We’ve put together a simple list of Turkey Hunting Essentials that will hopefully help you out as you make the next step into the exciting side of Turkey Hunting.

1. Turkey calls: Turkey calls are essential for attracting turkeys. There are different types of turkey calls, such as box calls, slate calls, mouth calls, and locator calls. You may want to bring a few different types to see which one works best for the turkeys in your area. Box calls are always an easy first introduction to calling and easier to use then mouth calls.

2. Camouflage clothing: Turkeys have very good eyesight, so you’ll want to wear camouflage clothing that matches the environment you’ll be hunting in. Make sure to wear a camo hat, face mask, and gloves as well.

3. Turkey decoys: Turkey decoys can be effective in luring turkeys into range. There are different types of decoys, such as hen decoys, jake decoys, and tom decoys. Depending on the season and location, different decoys may work better.

4. Shotgun: A shotgun is the most popular firearm used for turkey hunting. A 12-gauge shotgun is the most common, but a 20-gauge can also work. There are even .410 options that can work well. Make sure to use turkey-specific loads that provide enough shot density and penetration to take down a turkey.

5. Ammunition: As mentioned, turkey-specific loads are essential for hunting turkeys. Look for shotshells that are specifically designed for turkey hunting and have a shot size of #4, #5, or #6.

6. Turkey vest: A turkey vest can hold all of your turkey hunting essentials, such as calls, ammunition, decoys, and more. It can also provide some cushioning when sitting on the ground for long periods of time.

7. Safety gear: Safety should always be a top priority when hunting. Make sure to wear a hunter orange hat and vest when moving to and from your hunting location especially when hunting on Public Lands.

by Pursuit | Apr 20, 2023 | Gear, Hunting

Slayer Calls Turkey Mouth Calls are an exceptional product for turkey hunters looking for an effective and reliable way to attract game. The quality of the materials and craftsmanship is immediately apparent upon first inspection, with each call featuring precision-cut latex reeds and a durable aluminum frame.

One of the standout features of these mouth calls is their versatility. The set includes three different calls, each with its unique tone and pitch, allowing hunters to experiment and find the perfect sound to draw in their target. The calls are also easy to use, making them a great choice for both beginners and experienced hunters.

In terms of performance, Slayer Calls Turkey Mouth Calls deliver excellent sound quality. The calls produce a realistic turkey sound that is sure to grab the attention of nearby game. Additionally, the calls are designed to be durable and long-lasting, ensuring that they will hold up to repeated use in the field.

Overall, I would highly recommend Slayer Calls Turkey Mouth Calls to any turkey hunter looking for a high-quality product that delivers on both performance and durability. These calls are an excellent investment for anyone who takes their turkey hunting seriously.

Buy Now

by Pursuit | Apr 13, 2023 | Hunting, Inside Pursuit

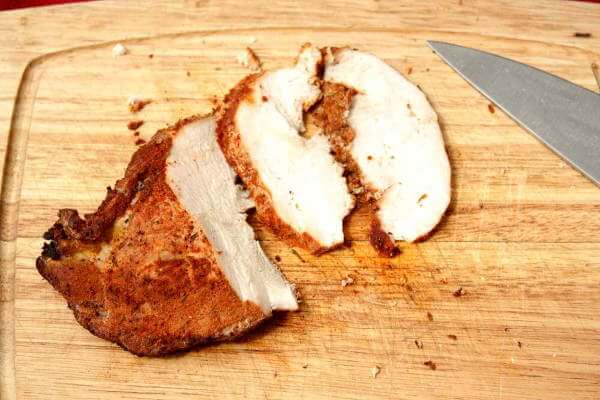

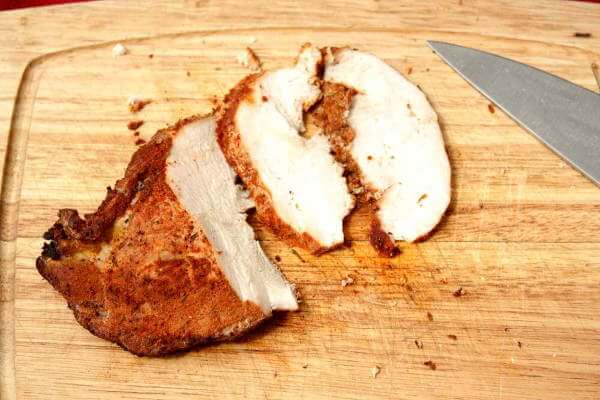

One of our favorite wild turkey recipe’s is smoked turkey breast. Here’s a simple recipe to try:

Ingredients:

• 1 wild turkey breast

• 2 tablespoons olive oil

• 2 tablespoons poultry seasoning

• 1 tablespoon salt

• 1 tablespoon black pepper

• 1 tablespoon garlic powder

Instructions:

1. Preheat your smoker to 225°F (110°C).

2. Rinse the turkey breast and pat it dry with paper towels.

3. Rub the olive oil all over the turkey breast, making sure to cover it evenly.

4. Mix the poultry seasoning, salt, black pepper, and garlic powder in a small bowl.

5. Rub the seasoning mixture all over the turkey breast, making sure to cover it evenly.

6. Place the turkey breast on the smoker rack, making sure there is enough space for the smoke to circulate around the meat.

7. Smoke the turkey breast for 2-3 hours, or until the internal temperature reaches 165°F (74°C).

8. Remove the turkey breast from the smoker and let it rest for 10-15 minutes before slicing and serving.

Note: Make sure to follow all safety guidelines for handling and cooking wild game. It’s important to fully cook wild turkey to ensure it’s safe to eat.

by Pursuit | Apr 13, 2023 | Hunting

There are numerous locations for spring turkey hunting across the United States, each with their own unique characteristics and challenges. Here are some of the top locations to consider.

Texas: Texas is a top destination for turkey hunting, with an abundance of Eastern and Rio Grande turkeys spread throughout the state. The terrain varies from rolling hills to open prairies, providing hunters with a diverse range of hunting opportunities.

Florida: Florida is known for its Osceola turkeys, which can only be found in the state. The hunting season is relatively long, and the birds can be found throughout the state’s varied landscapes, including forests, swamps, and agricultural areas.

Kansas: Kansas is home to both Eastern and Rio Grande turkeys, with a healthy population of birds spread throughout the state. The terrain ranges from grasslands to wooded hills, providing hunters with a variety of hunting opportunities.

Missouri: Missouri is known for its abundant population of Eastern turkeys, which can be found throughout the state’s wooded hills and river valleys. The state offers a long hunting season, and hunters are allowed to harvest two birds per season.

Alabama: Alabama is home to Eastern turkeys and has a relatively long hunting season. The state offers a diverse range of terrain, including forests, hills, and agricultural areas, providing hunters with plenty of hunting opportunities.

South Carolina: South Carolina is home to Eastern turkeys and offers a long hunting season. The state’s varied terrain includes mountains, forests, and agricultural areas, providing hunters with a range of hunting opportunities.

Ultimately, the best spring turkey hunting location depends on your personal preferences and hunting style. Be sure to do your research and choose a location that offers the type of hunting experience you’re looking for.�