Why Pocket Water is the Coolest Spot to Catch Summer Trout

Here’s how to pick off trout in high-water streams with a simple nymphing rig. Also, be prepared to get soaked

From the bank, I pulled the knot tight on my dropper fly and looked out over the river, which sent a quick shiver of fear knifing through my excitement, like the feeling you have before you get on a carnival ride. The river was up, hurtling foam over the boulders after one of those long summer rainstorms that leaves wisps of steam spiraling above the fields—exactly how it looked when my grade-school buddy Jo and I first fished the spot, years ago.

Jo had a reputation as a tough kid. (Nobody pointed out to Jo, for example, that only girls spell that name without the e.) The river didn’t scare him. He hiked the worm box—filled with night crawlers we’d pinched in the rain the night before—from his waist to his armpits and cinched the belt across his chest. Then he dropped in and battled the current to a rock below a roaring plunge pool.

It was when he turned and motioned for me to wade in that his sneakers began to slide, and he started flailing in vain to catch his balance. The worm box popped open. Night crawlers sailed. And in the boiling slick below, where the fat morsels plopped and raced downstream, a yellow slab rose and parted the surface.

It was the biggest trout I’d ever seen.

After that, I wasn’t scared either. I jumped in and lobbed a crawler into the slot—and the brown crashed and bolted downstream. As I leaned into the fish, my sneakers shot in opposite directions, and I rode the current downstream, rod held high above the froth. But when I finally got my footing, the fish had broken off.

Upstream, Jo was laughing. Since we were both soaked, we spent that day wading or swimming to the river’s hardest-to-reach holes—and had one of the best days of summer fishing I can remember.

Make It Easy

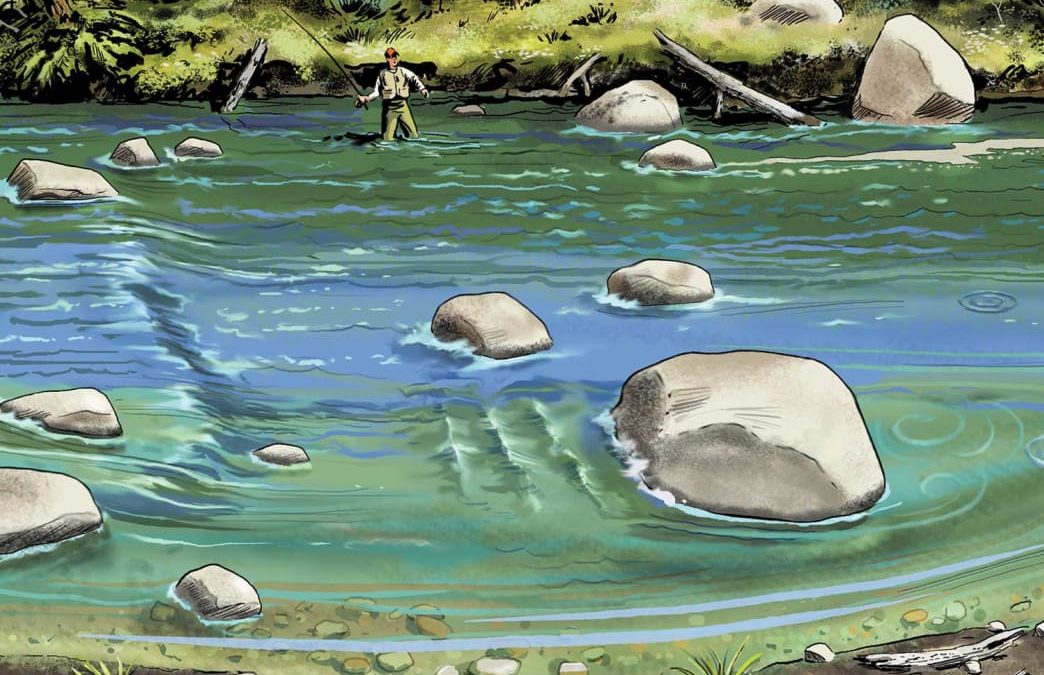

In midsummer, I want to be waist-deep in heavy pocket water, when the river is up and the fishing turns on. I don’t lob crawlers much anymore—not because I think I’m above it. I just think flyfishing is more fun. And summer should be fun.

Summer should also be easy. It’s a nice coincidence that if there is good rainfall, pocket water can fish well through the hotter months. By then, I need a break from all the fussing that goes with slow-water dry-fly fishing, and pocket water is the perfect antidote. It’s one of the rare things in life where you can take the easy road and not give up any success.

The easy road, from a technical fishing standpoint, is to put a strike indicator above a subsurface fly or two on a 9-foot 5X leader and walk up the middle of the river, picking pockets left and right. You can make it more complicated. You can study the water as if reading it were a form of code-breaking. But why would you? The fish are in the slower spots next to the faster spots. And eager. Make a decent drift, and they’ll usually grab your fly.

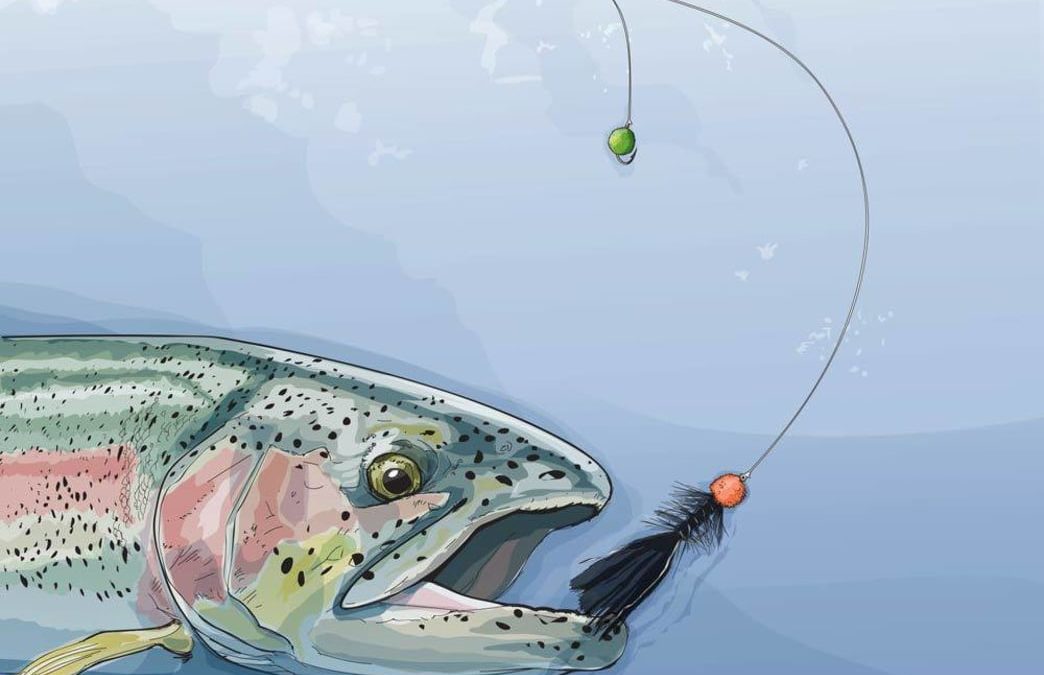

Just about any pattern that looks like trout food (and plenty that don’t) will catch fish in pocket water now, but as a general rule, I think it’s tough to beat a weighted stonefly nymph with a Muddler Minnow dropper. If there are more rainbows than browns, I’ll swap the Muddler for a Woolly Bugger. It just seems to work better. Choose a pocket or seam, wade close, and cast above it with a little flick of your wrist to drive the flies under. High-stick them through the sweet spot, then let the Muddler swing down and across before you pick it up. If the trout don’t seem active enough to chase a streamer, switch to a small nymph or wet fly. That’s it. Work fast, and cover a lot of water.

And don’t be afraid to get soaked. Put on some wet-wading shorts and jump in. This might sound crazy, but after nearly 40 years of fishing pocket water, I’m convinced that when flows run high and fast, nothing increases the number and size of the fish you catch more than simply wading aggressively. I don’t say recklessly—you need to stay safe. And I don’t wear sneakers anymore. Studded wading boots help, and a collapsible wading staff is handy in the roughest patches. Just remember that in heavy water, it’s the hard-to-reach spots that hold the neglected, and often bigger, fish. And you can’t rely on long casts to reach them. With so many intervening currents, pocket water forces you to wade close, often real close, to get a decent drift.

Redemption Time

Back on the bank, I took one step into the drink and went in to my waist, then I fought my way to the slick below the roaring plunge pool where I’d lost that huge yellow slab years ago. Halfway into the drift, my indicator stopped. But this time the fish ran upstream instead of down, and I landed it in a shallow side eddy. My tape read 23 inches—the biggest brown trout I’d ever caught in a freestone stream, along with a nice dose of redemption. And I didn’t even have to go swimming. Summer fishing doesn’t get much easier—or more fun—than that.

Gear Tip: Take it to the Top

Midsummer can have sporadic but good surface stonefly activity. So bring a handful of big, buoyant stone imitations, like Stimulators or Sofa Pillows. Grease them up and skitter them over the soft spots about an hour before dusk, or if you see big bugs popping. You won’t catch any more fish this way, but you’ll watch some big trout roll and slash. And as long as you remember to beef up your leader to at least 3X, you’ll land a few of them too.

Written by David Hurteau for Field & Stream and legally licensed through the Matcha publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to legal@getmatcha.com.

Featured image provided by Field & Stream