The Craft Lager That’s Saving Our Rivers

Why a brewer of fine beers is fighting to keep our water sparkling, our trout frisky, and our brews crisp.

Way back when, about 11 years ago, long before quality craft beer in a can was much of a thing, Upslope co-founder Henry Wood was catching up with his old NOLS instructor colleague and pal Tom Reed—Trout Unlimited’s Angler Conservation Program Director—over a beer. Reed wanted to take the conservation group’s 1% For Rivers program national. And Wood was gearing up to do the same with their new Colorado born Craft Lager. If you’re envisioning some affirmative head-nodding you have the right idea. The gist of it? Buy a Craft Lager and one percent of the gross sales goes to the Trout Unlimited chapter in the state where you bought it. That’s “gross” not “net,” which translates to no small sum. Since just 2015, Upslope has donated $60,000 to the cause. “Beer and trout have a lot in common,” says Reed. “They both depend on clean water.”

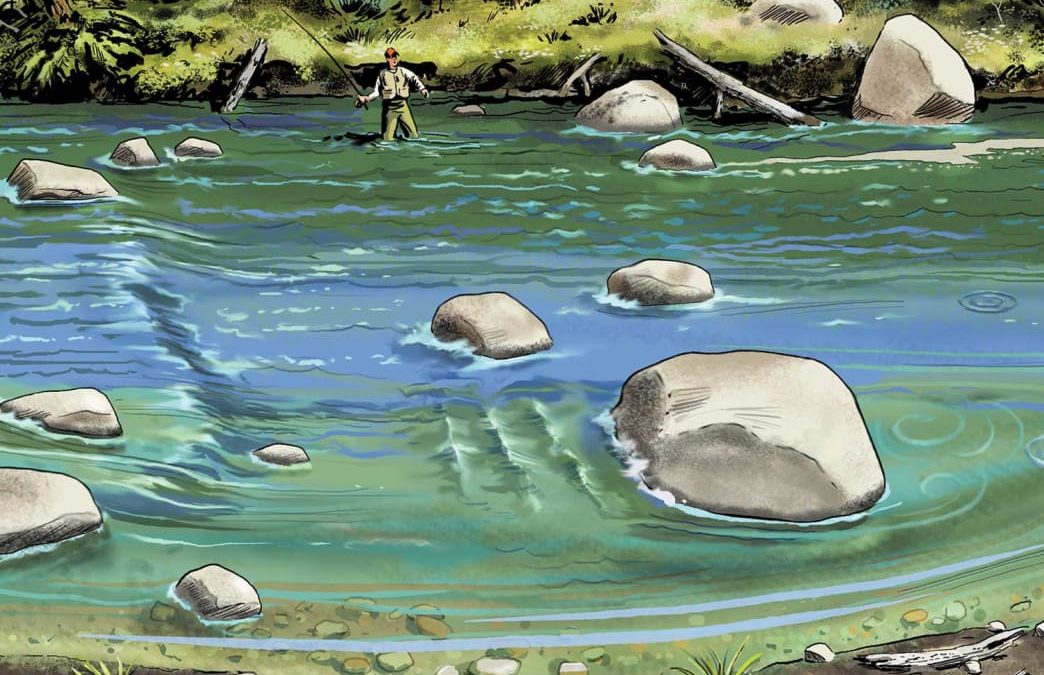

Fishing and Craft Lager, A Great Pairing

What you drink matters. That’s true regardless of your passions, but if you’re into fly fishing, it’s especially relevant. Why wouldn’t you buy a beer that helps restore and protect rivers? Also, Craft Lager comes in cans, which are the perfect vessels for your vessel. Cans are lighter to ship, reducing the carbon footprint, and they’re easier to recycle than glass. There’s almost no waste: If Americans recycled every can, 96 percent of that aluminum would get repurposed. As for pairing, it doesn’t hurt that this crisp, straw-colored lager is sessionable. “It’s an easy drinking, 4.8 percent alcohol, American made all grain lager,” says Wood. “It’s tough to crush higher alcohol IPAs and steer a driftboat.”

The Upslope Crew Walks the Talk

Just as it’s hard to find a mountain biker or hiker that doesn’t see the value of spending an afternoon standing in a cold stream with a rod in hand, it’s hard to find an Upslope employee that isn’t willing to wade into river conservation work. “Beyond our donations to Trout Unlimited, we’ve physically done stream restoration as a company for years,” says Wood. “We coordinate with Rocky Mountain Anglers here in Boulder on Boulder Creek, and on South Boulder Creek in Eldorado Canyon State Park pulling out weeds and rebuilding banks. Our employees get two paid days off a year to donate their time to nonprofit work.”

The Smith River Thanks You

Like the Grand Canyon is to whitewater boaters, the Smith River in Central Montana is to fly fishers—one of the crown jewels. As such, it’s the only float in the nation that requires a permit—which you draw for much like choice elk habitat. To call that float “coveted” would be an understatement. But now a proposed hard rock copper mine on Sheep Creek near the put-in for the Smith is jeopardizing that storied waterway. With money that comes in part from Craft Lager sales, Trout Unlimited is paying lawyers to fight the Australian company pushing the mine and hiring an educator to travel the state singing the virtues of the Smith. “There’s a checkered history of hard rock mining in the state of Montana,” says Reed. “But even though Montana’s mining laws are friendly to international corporations we’ve given them a good fight. We don’t think that’s an appropriate place for a mine. And we aren’t alone. We have good grounds for a lawsuit. I’m hopeful that with continued support t we’ll win.”

Upslope’s Commitment Has Only Grown

Upslope is now one of only two certified B Corp breweries in Colorado, and one of only about 30 worldwide. What’s that mean for the average fly fisher in search of malted beverages? A lot actually. B Corp status depends on a commitment to three overarching promises to take care of employees, the community that the business touches, and the environment. Because Upslope has been committed to such goals since day one, it earned B Corp certification on the first bid. Now the challenge is to constantly improve to meet B Corp’s evermore exacting standards. Much of that challenge falls on Upslope Sustainability Coordinator Elizabeth Waters—who started out at the brewery in the tasting room as a bartender with an environmental degree. “Our biggest blind spot was our supply chain,” says Waters. “Unlike employee benefits and environmental initiatives, we didn’t have any set policy around how we source materials. Now we’re chipping away at it vigorously. It’s the little things that add up. And those little actionable initiatives get identified by our employees. Like when a hops supplier recently switched from non-recyclable paper bags lined with plastic to full paper. That simple move keeps tons of waste from the landfill. We hope to be 85 percent to our zero waste soon.”