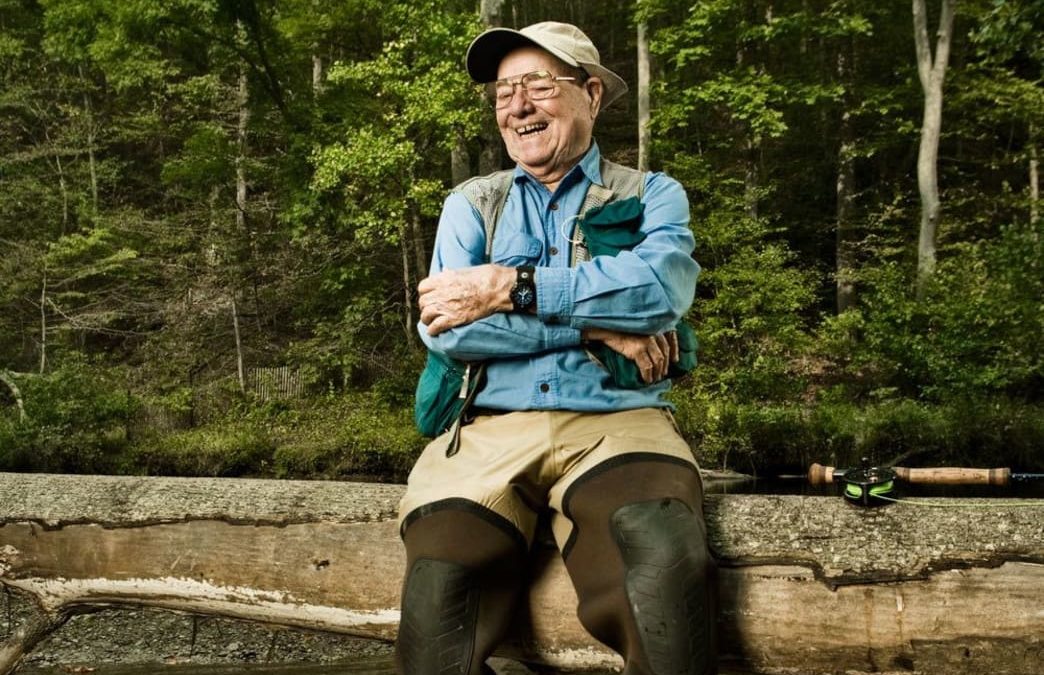

How I Fish: Lefty Kreh

One of the greatest flyfishermen of all time shares his angling wisdom, talks about his favorite fishing spots and fish to chase on the fly, and explains his four principles of fly casting

Lefty Kreh, one of the most accomplished and beloved flyfishermen of all time, died in 2018. He was 93 years old. Kreh was a prolific author and globe-trotting angler. Among his many accolades, Kreh was the winner of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Sportfishing Association and a member of the IGFA Hall of Fame and Flyfishing Hall of Fame. He was also a wonderful person—kind, warm, funny, and always happy to teach others. Field & Stream’s legendary fishing editor John Merwin once wrote of Kreh: “If America can claim a national flyfishing treasure, Lefty is it.”

Here, we’re reprinting an interview Kreh gave the magazine back in 2009. His stories, humor, and fishing tips are timeless—just like the man himself.

I’ve been fishing since I was old enough to walk to the Monocacy River, near Frederick, Md. My father died when I was young, during the Depression, and my mother had to raise four children. I was the oldest, at 6. We were so poor that we had to live on welfare. I’d catch catfish on bait and sell them so I could buy clothes and food to get through high school.

After World War II, I started fly casting when I got back from Europe. (Lefty fought in the Battle of the Bulge in 1945). Back then, I got a job at the Biological Warfare Center, where we grew and concentrated the bacteria that the scientists worked on. I was one of three people who got anthrax—on my hand and arm. My full name is Bernard Victor Kreh, and there is now a BVK strain of anthrax. I was doing shift work, and I’d hunt or fish between shifts. I started to get a reputation as a hotshot bass fisherman.

Joe Brooks, the fishing writer, lived in the Baltimore suburbs, and he was writing a column in the county paper. He came down with a fly rod one day. This was in September 1947. A big hatch of flying ants was trying to fly across the river, and millions of them were falling into the water. I’m using a 6-pound-test braided silk line, and Joe pulls out this fly line that looked like a piece of rope and swished it back and forth. There were rings out there—he was using a Black Ghost streamer—and he dropped this damn thing in a ring, and boom, he had a fish. He caught almost as many bass as I did, and you don’t normally do that to a guy on his own river.

The next day I drove to Baltimore in my Model A Ford and met him, and we went down to Tochterman’s Sporting Goods—it’s still there, third generation—where he picked out a South Bend fiberglass rod, a Medalist reel, and a Cortland fly line. We went out in the park, and he gave me a casting lesson. Of course, he was teaching that 9 o’clock to 1 o’clock stuff, like everyone was.

My favorite fish to flyfish for are bonefish, absolutely. In freshwater, I like smallmouth bass and then peacock bass.

The longer you swim the fly, the more fish you catch. Gradually I evolved the method that I now teach, where you bring the rod back way behind you on the cast. This accelerates the line, lets you make longer casts and, in turn, puts more line on the water.

I started fishing for smallmouths on the Potomac, at Lander, which is below Harpers Ferry. The river was full of big smallmouths. It was fabulous fishing.

In the 1950s, I went down to Crisfield on the bay. They had a crab-packing plant there, and at the end of the day they shoved everything they didn’t put into cans off the dock. It was the biggest chum line you’d ever seen. My buddy Tom Cofield and I knew about it, and the bass were all over the place. We were using bucktails with chenille, and the wing kept fouling on the hook. On the way home, I said to Tom, “I’m going to develop a fly that looks like a baitfish, that doesn’t foul in flight, that flushes the water when it comes out into the air and is easy to cast.” That’s how I came up with the Deceiver.

The first magazine story I sold was to Pennsylvania Game News. I got paid $89. We thought it was a fortune! It was on hunting squirrels from a canoe.

I teach four principles rather than a rote method of fly casting. The principles are not mine; they’re based on physics, and you can adapt them to your build. They are: (1) You must get the end of the fly line moving before you can make a back or forward cast; (2) Once the line is moving, the only way to load the rod is to move the casting hand at an ever increasing speed and then bring it to a quick stop; (3) The line will go in the direction the rod tip speeds up and stops—specifically, it goes in the direction that the rod straightens when the rod hand stops; and (4) The longer the distance that the rod travels on the back and forward casting strokes, the less effort that is required to make the cast.

My most memorable flyfishing experience was in New Guinea. There’s a fish there called a New Guinea bass—they spell it N-I-U-G-I-N-I. They are the strongest fish I’ve ever seen in my life.

My three favorite flyfishing spots in the world are Maine for smallmouths, Los Roques off Venezuela for bonefish, and Louisiana for redfish. The marsh near New Orleans is over 20 miles wide and 80 miles long. There’s very light fishing pressure, and it’s absolutely the best redfishing anywhere.

The three most important fly casts are the basic cast —you have to learn to use a full stroke; a roll cast, because you use it for all kinds of things; and the double haul. You need to learn how to double haul.

Up until seven, eight years ago, you couldn’t get into flyfishing if you didn’t have a lot of money. Now we have fabulous rods. If you buy any rod today that costs more than $100, it will probably cast better than the person who buys it.

Written by Jay Cassell for Field & Stream and legally licensed through the Matcha publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to legal@getmatcha.com.

Featured image provided by Field & Stream