Eight Rules of Flyfishing for Late-Summer Smallmouths

Hit the water with these modified trout fly tactics to hook dog-day bronzebacks

Summer can be cruel to a devout trout fisherman. I found that out during the relentless drought of 2016. By July, flows on the Farmington River—my home water in Connecticut—were reduced to a pathetic 60 cubic feet per second. It looked more like a rock garden than a river, forcing its browns to huddle up in scattered cool-water refuges. I had no choice but to give them a rest.

Still, it was summer and I wanted to flyfish. Luckily the nearby Housatonic was there to give me a fix. It was warmer than the Farmington, but its natural flow was a bountiful 250 cfs. And it held a thriving population of smallmouth bass. Though I’d fished for “Housy” smallmouths on and off over the years, last summer I piled up my trout fishing chips and went all in on bronze. Focusing exclusively on smallmouths for an entire late-summer season gave me a true crash course in the methods and approaches that can make or break you on a summer bass wade. There are certainly similarities between targeting skinny-river smallmouths and trout, but you can forget about micro bugs and 12-foot leaders. Here are the most critical smallie lessons I learned.

Don’t Be Dainty

Have you ever thrown an articulated streamer into a pool of delicately sipping trout? At best, the fish will ignore it. At worst, they’ll scatter. Not so with smallies. Part of what makes them such exceptional fly targets is that going bigger, louder, and gaudier often draws more strikes when the action is slow than going dainty does. One evening, I was frustrated by a pod of bass that were taking small insects off the surface. Despite my impeccable drifts, they’d have nothing to do with my size 18 Light Cahill. Out of frustration, I tied on a big, ugly deer-hair streamer. Just before it hit the water, a 16-inch smallie exploded from below and snatched the bug clean out of the air. I was stunned. When was the last time you saw a trout do that?

Get Big and Weird

Subtle and sparse are not words commonly used to describe smallmouth flies. In-your-face is more like it. I knew smallies would hit Woolly Buggers and basic baitfish imitations, but I wanted more options. An online search led me to the TeQueely. With a flashy body, contrasting marabou tail, chartreuse wiggly legs, and beadhead, the TeQueely looks like nothing in particular, but the bass treated this mash-up pattern like their first meal in days. Aside from trying oddball flies, don’t be afraid to chuck larger patterns than you might normally use for bass to keep little smallies from attacking your bug before heavier fish can. I learned this trick from former Housatonic guide Torrey Collins. “My favorite streamer there was a rabbit-strip leech with a conehead,” Collins says. “I always tied them at least 4 inches long to get past the pipsqueak fish.”

Mix It Up

Trout will turn their noses up at anything but the perfect imitation of that moment’s hatch. Smallies don’t. That frees you up to use a variety of different patterns and presentations to see how the fish will react. During an outing, I’d switch from a conehead streamer to an old-school soft-hackled wet fly to a popper to a classic Catskills dry in the span of an hour—and I’d catch smallmouths on all four. Even when the renowned Housatonic white fly hatch was going off in August, attractor flies like an Adams or a Stimulator would get sucked down as quickly as a genuine white fly pattern. If you’re not seeing surface activity on dries or poppers in rivers with a strong crayfish population, Collins says, a dead-drifted earth-toned Woolly Bugger can be lethal. Nymphs can be fished deep along the bottom or as a dropper off a dry. No matter the approach, smallies don’t require a perfect presentation; in fact, they’ll go out of their way to chase down a meal. You’ll catch plenty of fish even if you’re lacking a bit in the accuracy department.

Fear No Frog Water

Smallmouths are ambush feeders, so unless there’s a hatch they’re keyed into, these fish are less likely than trout to hold in open runs. With that in mind, avoid featureless areas and extreme shallows. When you get to the river, target structures like downed trees, submerged logs, boulders, pocket water, and underwater ledges. One other major difference between trout and smallies is productivity in frog water. Stretches of still water tend to be worth fishing for trout only when they are rising, but that’s not the case with bass. Slow-water trout have a lot of time to look at a fast-moving fly, which makes them difficult to fool on streamers. Smallmouths are more likely to charge than study, and the reedy edges of frog water make great ambush points. Whenever you hook a smallmouth near a prime ambush point, keep fishing that area for a while, because where there’s one, there are usually more.

Work the Cafeteria Line

One of the best places to find smallies is in what I call the cafeteria line, and it’s easy to spot. Look for a distinctive foam line gathered on the surface, as such lines indicate the heaviest, deepest flow in any given section of river. This is significant, especially in the low, warm-water conditions you’re likely to encounter during the dog days. Compared with other parts of the river, the cafeteria line offers lots of dissolved oxygen, food, and cover. Focus your drifts and streamer strips through its softer edges. As long as they’re not too shallow, gravelly riffles and their dump-in points at the heads of pools are also prime smallie real estate.

Harness Magic-Hour Power

You can catch smallies at high noon, and there’s definitely something liberating about wet-wading a river on a scorching summer day. But dawn and dusk are truly magical times. Low-light conditions—particularly the first or last hour of light—turn smallmouths into reckless marauders. I’ve caught dozens of smallies at sunset in runs where I blanked a few hours earlier. In low light, you’re also more likely to encounter bigger fish that have spent the day lazily holed up. Once the sun dips behind the hills, the water temperature will begin to drop, and by dawn it will be at its coolest. It’s during these brief periods that the wise, old fish are going to grab a meal. If you must fish under the blazing sun, target shade lines from bankside trees, any area in full shadow, and deeper runs or holes.

Use a Trout Stick (With a Kick)

Last summer, I used a medium-fast-action 10‑foot 5-weight on almost every trip. Collins favors a 10-foot 6-weight or a 9-foot 7-weight. Choosing the proper setup really boils down to the flies you’ll be throwing, the size of the river you’ll be fishing, and the average size of the smallmouths you’ll be fighting. If you don’t want to bulk up your outfit, one way to keep your rod light and still throw fairly bulky flies is to fish a line that’s heavier than what’s printed on the rod’s blank. Last summer I used a long-bellied, weight-forward 7-weight floater with my 5-weight rod, and I was able to cast even larger articulated flies with ease. If you’re looking for an excuse to buy that new sealed-drag reel you’ve been eyeing, this isn’t it. Sure, smallmouths hit like a battering ram, cartwheel like steelhead, and dig in their heels like a stubborn teenager, but you won’t see your backing. My standard-issue trout reel handled every fish.

Lead With Authority

If you’ve ever been frustrated by diagrams of Euro-nymphing trout leaders, some of which require an engineering degree to decipher, you’re going to love the fact that your smallie leader can be a straight shot of 8- to 15-pound-test fluorocarbon. If you need help turning larger flies, add a simple butt section of 15- to 20-pound-test fluoro. Don’t want to build anything? Grab some 0X to 3X tapered leaders at the fly shop. For fishing dry flies, I’ll use a 7½-foot 1X leader and splice some 4X tippet to the end. The goal with any leader for any presentation is strength, not stealth, as smallies aren’t often leader shy. Your leader should be strong enough to withstand the shock of a punishing hit, and it should enable you to put enough pressure on a fish to land it quickly for a healthy release with minimum stress on the bass.

Written by Steve Culton for Field & Stream and legally licensed through the Matcha publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to legal@getmatcha.com.

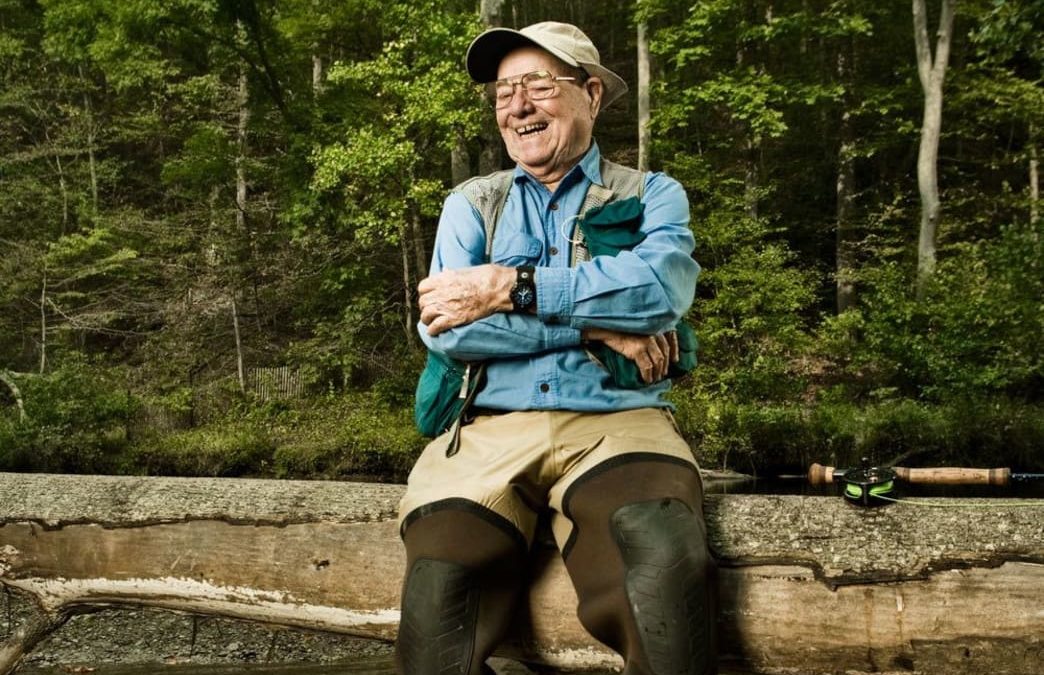

Featured image provided by Field & Stream