Learning to Fly Cast from an Angling Icon

After an injury stymies the author's fly-casting skills, he revisits lessons from the late, great Lefty Kreh and finds his stroke again.

I was recuperating from a broken wrist, which I suffered on a Montana trout fishing trip when my horse bucked as it stepped on a rattlesnake that had been mauled by a bear. In other words, I tripped on a rock while hiking back to my car and cracked the sesamoidal pisiform of my wrist. Right there at the triquetral joint. Ugh.

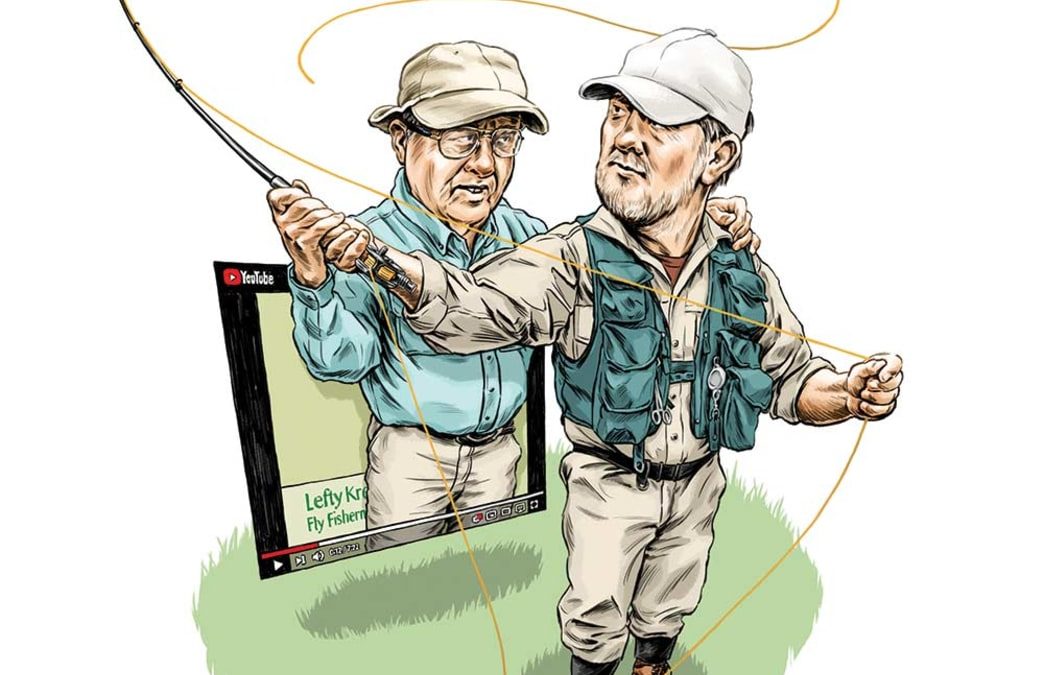

I knew I’d have to modify my fly-casting stroke while I regained strength and range of motion, and it so happened that I was working on a tribute to Bernard “Lefty” Kreh, the legendary flyfishing angler and instructor who had passed away just a few months earlier. Watching YouTube videos of Lefty casting was a revelation. At more than 80 years old, the man could cast 80 feet of fly line with all the drama of opening a can of soda. As I pecked away, one-handed, on my story, I thought: If I have to relearn a little, maybe I should start at the beginning.

After all, I’d been thinking about the mechanics of my fly casting for a while. For years, I had been using a Kreh-like total-body casting stroke, but as I threw ever-heavier lines with ever-heavier rods, all sorts of unnecessary gesticulations crept into my style. I had begun raising my casting arm to squeeze more rotation from the shoulder. I would punch the rod forward like I was taking an angry swing. I could sense that my casting was getting out of hand, and then I had a chat with Flip Pallot, the second most famous flyfisherman of all time. He told me that in 1964, when he was already a hotshot South Florida flyfishing guide, he saw Lefty cast an entire fly line with his bare hands. “I knew right then,” Pallot told me, “that I might know how to catch fish on a fly, but I didn’t know shit about fly casting.”

It was, most likely, the only time that Pallot and I will ever feel the same way about our casting skill. It was time to go back to school.

Casting Calls

Over the next few weeks, I propped my laptop on a chair in the backyard, pulled out a rod, and let virtual Lefty reteach me how to cast. He espoused what he called the Four Principles of Fly Casting. Like gravity, they could be neither altered nor ignored. Most are standard fare among casting instructors: The fly must be moving before you begin the backcast. Don’t bend your wrist, or you’ll waste a cast’s energy by throwing the line in a curve. The line will continue in the direction where the rod tip stops.

But it was Lefty’s “head to toe” casting style that set him apart from many. He eschewed the metronomic 10 o’clock to 2 o’clock cadence that most fly casters first learn. From the shade of my pecan tree, the World War II veteran dismissed this as “saluting.”

“What are you, a windshield wiper?” YouTube Lefty asked. “In no other sport do you only use your hand and arm. From Frisbee to ping-pong, you use your whole body.”

For Lefty, the perfect fly cast started at the ankles, knees, and waist as he twisted 45 degree away from the target and brought his casting arm behind his shoulder. He waited for the fly line to flatten out behind him, then he'd reverse courdse, with a smooth forward cast that picked up speed from starts to stomp-on-the-brakes finish.

For Lefty, the perfect fly cast started at the ankles, knees, and waist as he twisted 45 degrees away from the target and brought his casting arm behind his shoulder. He waited for the fly line to flatten out behind him, then he’d reverse course, with a smooth forward cast that picked up speed from start to stomp-on-the-brakes finish.

I mimicked his power stroke, threading the fly line in the open airspace between the back deck and the pecan. I had to raise the rod tip a smidge for the line to clear the neighbor’s fence on the backcast, but I’m sure Lefty understood that I was working in a tight space. But otherwise, he let nothing slide. He admonished my hand position on the cork. “Thumb behind the target!” He called out my snapping strokes. “Accelerate through the stroke! You don’t have to work any harder to cast 60 feet than 20 feet!”

I practiced turning my body toward the backcast and keeping my elbow low. “Don’t ever lift it off the shelf,” Lefty explained as I replayed the clip a dozen times. I started my casts farther back, focusing on a smooth acceleration from start to finish.

“That’s right!” Lefty hollered out, both to me and to some young woman standing by a farm pond on the computer screen. “Casting too hard is how you get wind knots when there ain’t no wind!” We practiced day after day as Lefty admonished me from the bow of a flat skiff in the tropics, from years and decades long past. My wrist began to complain less and less, and my fly line loops tightened.

“You don’t cast a fly line, you unroll it…. A backcast ain’t nothing but a forward cast going the other way…. Get the fly moving!” Lefty barked from the laptop’s tinny speaker.

A month later, laptop Lefty was, unfortunately, nowhere to be found. I motored out of North Carolina’s Beaufort Inlet with a grimace; a 20-knot wind chopped the water into 3-foot waves, each curl capped with white foam. Scattered schools of Spanish mackerel and false albacore popcorned around the tide break, but the fish were up and down so quickly, you’d miss every chance with a four-stroke false cast. I eased upwind of the fish and listened to Lefty’s words in my head. I slowed each cast down. With my arm locked to an imaginary shelf, the cast’s low center of gravity helped keep my feet bolted to the hull. I turned my body toward the backcast, Lefty-style, and smoothly delivered a 40-foot zinger with a single backcast. I practically felt his hand slapping my back.

Then I missed the only solid strike I’d have that morning. I set the hook too early and practically ripped it from a mackerel’s mouth. Flustered, I heaved on the rod for the backcast instead of stripping the fly tight, and pulled a spaghetti wad of gnarled line straight into the hull. I had to laugh. If Lefty were watching, I knew what he’d say. I’d heard it a dozen times before.

“God ain’t gonna let you cast until you get the end of the line moving,” Lefty preached. “He just ain’t.”

So it was back to the basics. Seems like that always works best.

Gear Tips: Hot Rods

It isn’t suitable for every fishing situation, but the Sage Igniter rod series does what it is designed to do with a ferocious punch: deliver heavy lines and heavy flies through strong winds and over long distances. And it’s not just for the salt: A super-fast blank taper and light feel make these rods a potent tool for all-day casting from a drift boat.

Written by chillman for Field & Stream and legally licensed through the Matcha publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to legal@getmatcha.com.

Featured image provided by Field & Stream