Four all-American diners share their favorite breakfast recipes that you can cook at camp

Breakfast should be the official meal of opening day. You can get it at many local fish-and-game clubs on the opener. You can get it at deer camp, as long as someone gets up to cook. And you can get it at 4 a.m. at the Blue & White Restaurant in Tunica, Mississippi, on the opening day of duck season.

“All the guides bring their clients here for breakfast before the hunt,” says Steven Barbieri, co-owner of the Blue & White. “We’re like their headquarters. During the season, I’d say at least 70 percent of our customers are wearing camo, some still in their waders. Some even with paint on their face.”

To one degree or another, that’s the story this time of year at rural diners across the U.S. The “Hunters Welcome” signs go up, and we pile in. But if you can’t get to the local diner, you still need to have a killer morning meal on opening day—and these four belly-busting recipes, shared from some of the country’s best diners, will do the trick. Dig in, then get hunting.

Southern stack: Blue & White Restaurant’s 61 Hobo Breakfast

After the morning shoot, waterfowl hunters pile back into the Blue & White for a second breakfast, filling the 144-seat place to capacity. A favorite, says co-owner and kitchen manager Joe Weiss, is the 61 Hobo Breakfast. “It’s a big, messy stack of food that a hunter would cook at a duck camp.” In fact, a version of the dish was originally cooked at Weiss’ own Lazy Drake Duck Club.

You Will Need

Ingredients | Serves 1

- Hash browns

- Butter

- Onion

- Game meat

- Eggs

- Cheddar cheese

Directions

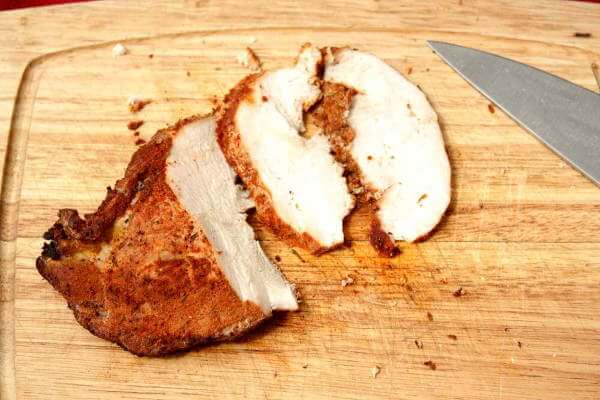

Start with a single portion of hash browns, which you can buy pre-made in the refrigerated section of the grocery store. Then melt butter in a large skillet and crisp the hash browns on one half of the pan. On the other half, sauté half a medium onion, cut into strips, and cook your protein. “We offer pork sausage, ham, or bacon, but venison sausage or duck breast would work great,” Weiss says.

Flip the hash browns, and then stack the onions and cooked meat on top. Then fry eggs to order and add them. Finally, sprinkle cheddar cheese over the whole mess and cover the pan to melt.

“It’s an absolute favorite with our hunters. I’m sure some of them order it once before the hunt and get it again after,” Weiss says.

Eastern Icon: Neptune Diner’s Country Scrapple

What’s scrapple? Commonly described as “Everything but the oink,” scrapple is a Pennsylvania Dutch treat of boiled pork offal mixed with cornmeal and formed into a loaf—then sliced and fried. It has a dedicated following in much of the Mid-Atlantic, and is a breakfast favorite at the renowned Neptune Diner in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Co-owner Alex Mountis says the diner sells so much scrapple that they source it from a local supplier. But having grown up in the area, Mountis can surely tell you how to make this Keystone State staple: “Typically, the meat is pork heart, liver, and butt, but it would be easy to substitute almost any game meat.”

You Will Need

Ingredients | Serves 4 to 6

- Game scraps and/or organ meat

- Spices

- Cornmeal

- Oil

Directions

Boil 11⁄2 pounds of meat scraps in 4 cups of water until the meat is very tender (at least two hours). Strain the broth into a saucepan. Run the meat through a grinder or zip it almost to a paste in a food processor. Bring the broth to a simmer and add the processed meat, as well as salt, pepper, and sage to taste. Slowly add cornmeal (about a cup), stirring constantly, until thick. Transfer into greased loaf pans, and refrigerate overnight. In the morning, cut into 1⁄4- to 1⁄2-inch-thick slices and fry.

“We’re best known for how we prepare it,” Mountis says. “You want it soft in the middle and golden and crispy on the outside. At home, you can fry it in a deep skillet with about an inch of high-heat oil, or pan-fry it with oil or butter, and use a light press to get the crust.” Serve scrapple as a side with eggs and pancakes or French toast. Some like it with ketchup, others with maple syrup. Try both.

Midwestern staple: Zingerman’s Roadhouse’s Famous Corned Beef Hash

You can get hash anywhere in the Midwest, but if you want “famous” hash in one of the country’s biggest deer-hunting states, you go to Zingerman’s in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Zingerman’s uses a corned beef recipe that originated in Detroit’s Eastern Market in the 1980s. But you’ll want to corn your own venison, which is a simple process of brining venison for a week, then boiling or steaming it until tender.

You Will Need

Ingredients | Serves 4 to 5

- Potatoes

- Corned venison

- Butter

- Onion

- Celery

- Red pepper

- Flour

- Chicken stock

- Worcestershire sauce

- Sage

- Heavy cream

Directions

Start by dicing 2 pounds of blanched, cooled potatoes and 2 pounds of corned venison. Mix them in a large bowl and set aside. In a skillet, melt a couple of pads of butter, and sauté 11⁄2 cups chopped onion, 3⁄4 cup chopped celery, and 11⁄2 cups chopped red pepper. Next add 6 tablespoons flour and mix well. Pour in 11⁄4 cups chicken stock, 11⁄2 tablespoons Worcestershire, and 1⁄2 teaspoon dried sage, and stir. Add 1⁄4 cup heavy cream, and salt and pepper to taste. Remove from heat and pour over the corned-venison-and-potato mixture. Use your hands to mix thoroughly. Now it’s ready for the griddle or frying pan.

Serve with runny eggs and sourdough toast.

Western Jefe: El Patron Café’s Huevos Rancheros

If you’ve hunted in the Southwest, you’ve probably had this Mexican breakfast classic and wondered why you can’t get anything quite like it anywhere else. The secret is the green chile sauce, which finds perfection in New Mexico. And the best green chile in the state, according to USA Today, is found at El Patron Café in Las Cruces. Here’s how chef Patrick Tirre makes it.

You Will Need

Ingredients

Game meat Butter Jalapeños Onion Garlic Flour Chicken stock Green chiles Tomatoes Spices

Directions

In a skillet, brown 11⁄2 pounds of meat, cubed into bite-size pieces. Chef Tirre uses pork shoulder or butt, but wild pig would work well, as would a mix of fatty pork and wild turkey, pronghorn, elk, or deer. When the meat is brown and crispy, splash in a little water in the pan to deglaze and set aside. In a pot, melt half a stick of butter and sauté 4 jalapeños, half an onion, and 4 cloves of garlic. Then add 3 to 4 tablespoons flour to make a roux. Next, add 2 quarts chicken stock, 16 ounces roasted, chopped green chiles (available in the Mexican section of the grocery store), and the insides of three hollowed-out tomatoes. Add the meat and season to taste with salt, pepper, cumin, and Tony Chachere’s Original Creole Seasoning. Finally, simmer until the meat is falling apart. Slap two or three corn tortillas on a plate, smother them with the meaty green chile, add two eggs any style, along with jack and cheddar cheese, and serve with flour tortillas to sop it all up. Serves 6 to 8

Written by Dave Hurteau for Field & Stream and legally licensed through the Matcha publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to legal@getmatcha.com.